Why Turkey’s Earthquake Was So Devestating

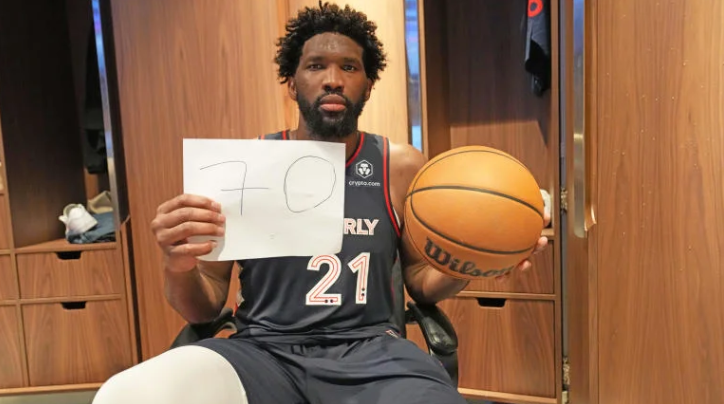

A massive earthquake struck near Adana, Turkey in February, causing poorly supported buildings to collapse. Photo by AP Photo (IHA Agency)

May 5, 2023

On Feb. 6, 2023, a series of intense earthquakes struck near Turkey’s shared southeastern border with Syria. According to the International Medical Corps, as of March 8, the death toll has surpassed 50,000 people, with 45,968 confirmed deaths in Turkey and 7,529 in Syria.

The first tremor was classified as a 7.8 magnitude shock, and according to Risk and Disaster Reduction Professor Joanna Faure Walker, only two of the deadliest earthquakes in the last 10 years have been of an equivalent magnitude. The earthquake struck on the lines of the North Anatolian and East Anatolian faults, along the converging points of the Anatolian, Arabian and African plates. Essentially, it was an area where high-intensity earthquakes are expected.

Yet, the power of the earthquake is not the sole reason it became Turkey’s deadliest natural disaster in modern history. The initial pair of 7.8 and 7.6 magnitude earthquakes were followed by strong aftershocks throughout the region. In addition, rescue missions were extremely delayed, with thousands of people still lying beneath the rubble weeks later. According to the Turkish government, more than 6,000 structures collapsed in the midst of the tremors – and much of this can be attributed to the manner in which they were constructed.

The majority of fallen buildings can be classified as soft-story structures, which are large buildings with multiple floors and can be found in countries like India, Pakistan and Turkey. The bottom of the structure is normally made of brittle concrete, while upper residential stories are made of stronger mixes of concrete and stone. The bottom is composed of an open floor plan that usually contains parking garages, small businesses or additional homes. This means that this floor will likely have fewer walls with open sides and columns that don’t have walls to connect them. Naturally, this makes the bottom story weak and incapable of properly supporting the stories above it. During earthquakes, the bottom story is particularly vulnerable to the unstable ground, and after powerful shocks, the bottom floor can collapse and bring the rest of the building down with it.

Since the earthquake hit Turkey in the middle of the night, most of its residents were asleep in their homes. The instant “pancake collapses” of residential buildings destroyed their homes in seconds and trapped many citizens under heavy construction materials, which complicated rescue efforts significantly. Furthermore, the earthquake’s epicenter included cities like Kills, Hatay and Gaziantep, which are located near the Syrian border and have become densely populated with Syrian refugees. More often than not, Syrians were forced to live in haphazardly-constructed buildings that weren’t properly maintained. When the tremors began, these weak structures couldn’t withstand the stress.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the first time that Turkey has seen massive death tolls due to the strength of their structures. In 1999, a comparable 7.6 magnitude earthquake struck Izmit and resulted in the deaths of over 17,000 individuals. The tragedy was significantly intensified because of poor building design, and according to the World Bank, soft-story collapses accounted for 90% of all destroyed buildings.

In the aftermath, the Turkish government began pushing for improved building codes that emphasized earthquake safety, but political corruption prevented the enforcement of these codes. Turkish construction companies continued to cut corners and ignore building codes, and the government allowed these violations to slide.

In addition, the majority of Turkey’s structures were built before 1999, which meant they could only be strengthened retroactively. This process involves reinforcing columns, open spaces and walls with steel frames and drilling bolts and braces into the foundation in order to provide the building with a better chance of supporting its own weight.

Unfortunately, retrofitting is extremely costly. The World Bank reported that about 6.7 million buildings throughout Turkey require structural refitting or reconstruction, amounting to a U.S. dollar equivalent of $465 billion. Suffice to say, as of 2021 only 4% of Turkish buildings have been reinforced.

The sheer difference that strong buildings make can be clearly seen in the small Turkish town of Erzin, which is located 50 miles from the epicenter of the earthquake. While the town still suffered minor building damage, the mayor stated that no buildings had collapsed and no one died. Although this is in part due to Erzin’s unique geography, the reduced destruction is also accredited to the lack of corruption within the town’s council and the strict enforcement of constructing buildings that are up to code.

Additionally, in the midst of buildings that had been reduced to concrete heaps, a brand new library in Adiyaman built by EU standards remained untouched. Despite the exterior of the building being fully constructed out of a glass facade, not a single window pane was cracked.

The devastating consequences of poor building construction extends far beyond Turkey. The catastrophic repercussions of the 2010 Haiti earthquake was similarly accentuated by the structural integrity of the structures. According to official records, 222,570 people were killed and 300,000 were injured. The Haitian government estimated that 250,000 residences and 30,000 commercial buildings had collapsed or endured severe damage. Thousands of these poorly designed buildings succumbed to comparable “pancake collapses” during the initial 7.0 magnitude earthquake and the aftershocks that ensued.

One month after the earthquake in Haiti in February 2010, Chile was hit by an 8.8 magnitude earthquake that caused about 500 deaths. A 2011 report by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction credited Chile’s “strict building codes” as a factor in the glaring deviation of deaths. Since then, the Chilean government has further improved the strength and safety of its structures. In 2015, the country experienced an 8.4 magnitude earthquake that triggered a tsunami on Chile’s western coast, yet only 13 people died.

Needless to say, the enforcement of building codes and the availability of safe housing plays a large role in the amount of damage and loss of life that an earthquake can cause. Perhaps the most tragic aspect of the Turkish disaster is the knowledge that, while earthquakes along fault lines are largely inevitable, many of these deaths could have been prevented.